All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Diversity of Woody Species and Biomass Carbon Stock in Response to Exclosure Age in Central Dry Lowlands of Ethiopia

Abstract

Objective:

Empirical evidence on the potential of area exclosure in the restoration of severely degraded lands is crucially important. Thus, a study was conducted to examine the influence of exclosure age on vegetation structure, diversity, and biomass carbon stock in the central dry lowland of Ethiopia.

Methods:

Exclosures of 5, 15, >20 years old, and adjacent open grazing land were selected. Data on vegetation were collected using 20 × 20 m sampling quadrats which were laid along parallel transect lines.

Results:

The result showed that 17 woody species which represent 9 families were recorded at exclosures and open grazing lands. Shannon-Wiener (H') diversity index ranged from 0.74 (open grazing land) to 2.12 (middle age exclosure). Shannon evenness (E) index was higher in the middle age exclosure (0.80). Woody species basal area and tree density significantly (p < 0.05) increased with increasing exclosure age. The Aboveground woody biomass significantly (p < 0.05) varied from 12.60 (open grazing land) to 68.61 Mg ha-1 (middle age exclosure). Similarly, the aboveground biomass (AGB) carbon stocked was significantly (p < 0.05) higher in the middle (32 Mg ha-1) and old age exclosures (31 Mg ha-1).

Conclusion:

This study indicated that exclusion can restore the degraded vegetation and sequester and stock more atmospheric carbon dioxide in the aboveground biomass. Therefore, open degraded grazing land of the lowland areas can be restored into a promising stage through area exclosure land use management.

1. INTRODUCTION

Land degradation which is a long lasting decline in the provision capacity of an ecosystem to provide goods and services (Appanah et al., 2015) is widely recognized as a serious global problem, particularly in developing countries. When coupled with climate change effects, it undermines food security (Etter, 2016). The Ethiopian highlands have been degraded and have reached catastrophic levels over the last three centuries (Berisso, 1995; Nyssen et al., 2015). The chief causes of land degradation in the country are population pressure and limited agricultural technologies, inappropriate land use and cultivation into marginal lands, and deforestation (Haile et al., 2006; Nyssen et al., 2008a; Hurni et al., 2010), socio-political changes (Dessie and Christiansson, 2008), and unbalanced free grazing with the still-increasing livestock populations (Taddese, 2001; Abiyu et al., 2011). Intensified use of land and dwindling of the remnant forests in central Ethiopia are further exacerbating land degradation (Abebe et al., 2014).

In Ethiopia, land degradation impairs the capacity of forests, to provide ecosystem services (Solomon et al., 2018) and the land to contribute to food security (Bishaw, 2001). It also results in significant environmental degradation and loss of forest biodiversity (Lemenih and Kassa, 2014). Estimates show that the country is losing up to 1636 km2 yr-1 forest cover, which is one of the highest in Africa (Tolera et al., 2008). Land degradation in Ethiopia has not only resulted in biomass loss, but also an increase in risks of desertification (Girmay et al., 2008). Further deforestation contributed to climate change by causing changes in the earth’s atmosphere in the amounts of greenhouse gases. Land resources degradation in Ethiopia resulted in erosion induced soil carbon depletion rate of up to 970 kg ha yr-1 (Shiferaw et al., 2013). Land degradation increases the vulnerability of people to the adverse effects of climate variability and change. As a result of unfavorable climate conditions, poor agricultural technologies, and high population growth, the magnitude of land degradation is more severe in arid regions of Ethiopia (Meaza et al., 2017).

The ecological restoration, which is the process of assisting the rehabilitation of degraded ecosystems (Ruiz-Jaen and Aide, 2005) has been an important approach to mitigate human pressures on natural ecosystems and improve ecosystem services (Mekuria et al., 2015). To rehabilitate the vast degraded landscapes and combat environmental problems, area exclosures have commenced since the 1980s in the northern highlands of Ethiopia (Aerts et al., 2009). Exclosures are areas that are excluded from the disturbance of domestic animals and humans to promote the natural regeneration of plants and reduce land degradation (Aerts et al., 2009). The ultimate goal of restoration using exclosure is to create a self-supporting ecosystem that is resilient to perturbation without further assistance (Ruiz-Jaen and Aide, 2005). Over the past two decades, exclosures have been expanded to the central part of the country (Mengistu et al., 2005; Yirdaw and Monge, 2018). Effective restoration of degraded ecosystems is one of the imperative efforts to ensure sustainable food and biomass supply to the heavily agricultural dependence of the population of the country while maintaining ecological integrity (Lemenih, 2006).

Restoration of degraded lands through the establishment of exclosures is crucial to support people and food systems as well as to adapt to climate variability (Mekuria et al., 2017). Studies have indicated that after exclosure was established on degraded landscape vegetation restored (Birhane et al., 2006; Mekuria and Yami, 2013; Mekuria et al., 2015; Ibrahim, 2016). Exclosures can enhance soil nutrients such as total soil nitrogen, available phosphorus, and cation exchange capacity (Descheemaeker et al., 2006b; Mekuria and Aynekulu, 2013; Abebe et al., 2014). Furthermore, exclosure can improve soil organic carbon (Yimer et al., 2015; Qasim et al., 2017) and increase the potential of atmospheric carbon sequestration (Feyisa et al., 2017). Area exclosures are likely to improve soil carbon stock thereby increasing the amount and quality of the biomass that is recycled into the soil (Chen et al., 2012). Restoration of vegetation in severely degraded lands in dry regions has a considerable potential to increase carbon storage while improving soil quality (Li et al., 2012).

Exclosure land management began to be practiced fifteen years ago to restore the degraded landscapes in Kewet district, which is part of the central dry lowlands of Ethiopia (Bizuayehu and Tefera, 2008). Unlike exclosures on other parts of the country, less attention has been given to exclosure in the central dry lowland of Ethiopia in the assessment of their effectiveness in the restoration of vegetation. Little is known about aboveground biomass and carbon stock of exclosures in response to their age (Giday et al., 2013). Earlier most studies conducted on area exclosures in Ethiopia focused on the comparison of vegetation composition and soil properties with adjacent grazing lands (Abiyu et al., 2011; Mekuria et al., 2018; Haftom et al., 2019). Except for very few (Descheemaeker et al., 2006a; Mekuria and Yami, 2013), change in vegetation composition along chronosequence is not yet well studied. Despite the number of studies, most studies lack integrating climate change issues i.e., determination of carbon stock. This helps the management and policy decision-makers related to the expansion of such land use management to restore degraded lands of the lowland areas. Therefore, this study aimed to quantify 1) the vegetation structure and diversity and 2) aboveground biomass and carbon stock of different aged exclosures and adjacent open grazing land in the central dry lowland of Ethiopia.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Description of the Study Area

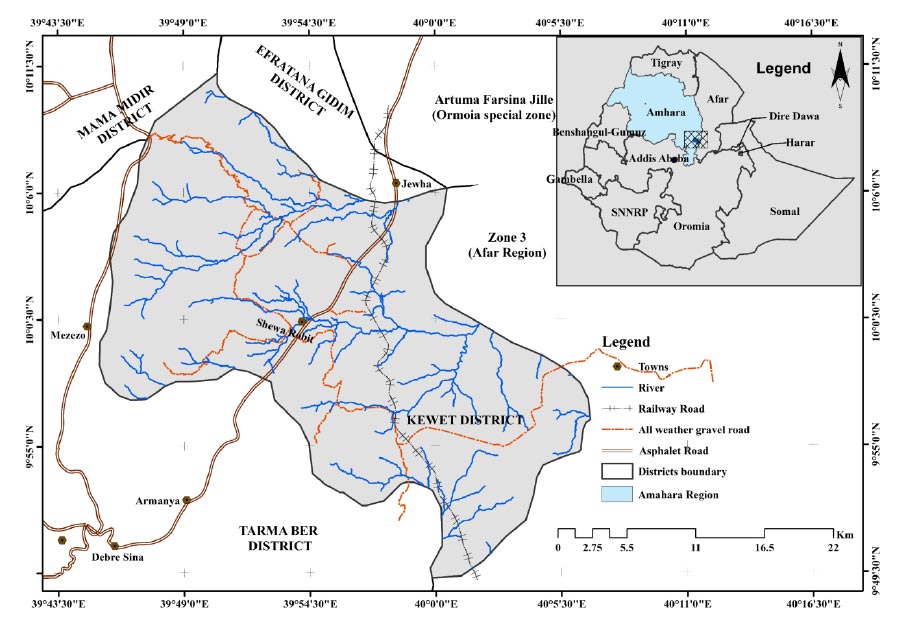

The study was conducted in Kewet district situated 213 km northeast of Addis Ababa at the foot of the eastern escarpment of the central Ethiopian highlands. It is located within the coordinates of 9°49′ and the 10°11' latitude N and 39°45′ to 40°6′ longitude E. Administratively, Kewet district lies within the North Shewa Administrative Zone of the Amhara National Regional State (Fig. 1). The altitude ranges from 1080 to 3151 m a.s.l. Based on 10 years (2007–2016) of data from the Shewa Robit meteorology station, the area receives a mean annual rainfall of 1007 mm and a mean annual minimum and maximum temperature of 16.5 and 31°C, respectively. Kewet district lay in Robit Valley which is widely covered by basalt and related pyroclastics rock types of tertiary age (Tefera et al., 1996). According to World Reference Base (WRB), Eutric Cambislos and pellic vertisols are the dominant soil groups in the alluvial fan area of the district lies the lower areas are dominantly covered with Calcaric gleysols and Calcic cambisols (Paris, 1986). Over 41 and 26% of the district’s land is covered by cultivated land, and forest and shrubland, respectively (Tesfay et al., 2020). Area exclosure practice is common in the district, which covers 15 km2 of the total land coverage (Bizuayehu and Tefera, 2008). According to Ethiopia’s Central Statistical Agency (CSA) population projection for all regions at wereda level from 2014 – 2017, the district has a total population of 147,093 with a population density of 197 persons per km2 (CSA, 2013).

2.2. Sampling Technique and Sampling Size

Three exclosure sites which are 5, 15, and >20 years old and one adjacent open grazing land were selected purposively which hereafter is referred to as young, middle, and old age exclosure, respectively. Then, three parallel transect lines (which were considered as replicates) across the selected exclosures and open grazing land were laid. Quadrats measuring 20 × 20 m (400 m2) were laid down along the parallel line transects at a regular distance (Kent, 2012). Data on woody species type, height, and diameter at breast height (dbh) of individuals with dbh > 2 cm were collected from quadrats along each line transects within each site. The total number of individuals of each wood species seedling and saplings < 1.5 m height was counted and recorded in each quadrat (Kent, 2012). Hypsometer and caliper were used to measure the height and dbh of the tree, respectively. A total of 36 sample plots was used to collect data on woody vegetation. The woody species were identified directly in the field using (Hedberg and Edwards, 1989; Edwards et al., 1995; Hedberg et al., 2003, 2006). Geographical information such as location, elevation, slope, and aspect of each plot was recorded using a geographical positioning system (GPS).

2.3. Vegetation Data Analyses

2.3.1. Floristic, Diversity and Structure Analysis of Woody Species

The similarity in the floristic composition of woody species between the different age of exclosures and adjacent open grazing land was computed using Sorensen's measure of similarity (Magurran, 2004) as follows:

|

(1) |

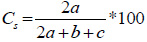

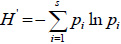

where, a = is the number of species common to both exclosures and adjacent open grazing land, b = is the number of species on exclosure 1 or adjacent open grazing land (site 1) only, and c = is the number of species on exclosure 1 or adjacent open grazing land (site 2) only. Often the coefficient is multiplied by 100 to give a percentage similarity figure. Species richness is a biologically appropriate measure of alpha (α) diversity and it refers to the number of species in a particular area (Newton, 2007). The diversity of woody species was determined by the Shannon-Wiener diversity (H') index. The index takes into account the species richness and the proportion of each woody species in all sampled quadrats (Teketay et al., 2018). Shannon-Wiener diversity was calculated using the following equation (Magurran, 2004):

|

(2) |

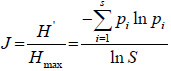

where, H’ = is a Shannon-Wiener (H') diversity index, Pi= is the proportion of individuals of woody species found in the quadrats, S= is the number of woody species and ln= natural logarithm. Woody species evenness which is a measure of similarity of the abundances of the different woody species in the sampled exclosure and grazing land sites (Teketay et al., 2018) was determined using Shannon evenness measure (E). It was calculated using the following equation (Magurran, 2004; Kent, 2012):

|

(3) |

The woody species structure was determined through quantitative analysis using parameters such as frequency, density (number of trees ha-1) and basal area (m2 ha-1). Frequency is the number of times a species is recorded in a given number of plots and it is expressed as the percentage of quadrats in which a particular species is present (Newton, 2007). Density is the number of individuals of a species per unit area (Kent, 2012). Basal area (BA) is the cross-sectional area of a tree estimated at breast height (1.3 m), which is expressed in m2. Basal area was calculated using the following equation (Newton, 2007):

|

(4) |

where: g = is a basal area (m2), and d = is the diameter at breast height of a tree (m).

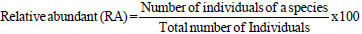

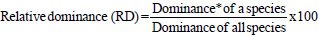

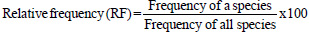

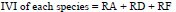

The importance value index (IVI) is used as a measure of species composition that combines frequency, abundance, and dominance values. The ecological importance of woody species (IVI) was determined using relative frequency, abundance, and dominance parameters according to the formula of (Kent, 2012):

|

(5) |

|

(6) |

|

(7) |

|

(8) |

where, *Dominance is defined as the mean basal area per tree, multiplied by the number of trees of the species.

2.3.2. Aboveground Woody Biomass and Carbon Stocks Estimation

To estimate the aboveground woody biomass (AGB) in the exclosures and adjacent open grazing land, an allometric equation developed (Tetemke et al., 2019) for multispecies of the dry Afromontane forests in dry mid-highlands of Northern Ethiopia was used.

|

(9) |

where, AGB = Aboveground biomass (kg tree-1) dbh = diameter at breast height (cm) rRMSE = relative root mean square error, and rBias = relative bias

Belowground biomass is often estimated from root: shoot ratios by taking 28% of the aboveground biomass ((Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) et al., 2006;) and it was estimated as follows:

|

(10) |

where, AGB = Aboveground biomass (kg tree-1)

Then both the above and belowground biomass were converted into carbon by multiplying the aboveground (or belowground) biomass by 0.47 (IPCC, 2006):

|

(11) |

where, Y = wood biomass-1 (kg)

2.4. Statistical Data Analysis

Data on vegetation structure, composition, aboveground biomass, and aboveground biomass carbon stock were subjected to a one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) following a generalized linear model (GLM) of SAS 9.2 software. Post Hoc Test of Tukey’s Honest Significant Difference (HSD) test was used for mean separation if the analysis of variance showed statistically significant differences (p < 0.05).

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1. Floristic Composition

A total of 21 species that represent 9 families were recorded both in the exclosures and adjacent open grazing land. Woody species richness ranged from 10 species in the open grazing land to 14, 15, and 17 species in the middle, old, and young age exclosures, respectively. This result is comparable to similar studies conducted by Haftom et al., (2019) in Tigray, Northern Ethiopia, and Abiyu et al., (2011) in South Wollo, Northern Ethiopia. which reported 17 and 14 woody species, respectively in area exclosures. However, the result of this study is lower when compared to reports of Mekuria et al., (2018) which reported 32 woody species in exclosures in the North-Western Ethiopia and Teketay et al., (2018) which recorded 35 woody species in an exclosure in the Mopane woodland in northern Botswana.

Analysis of the Sorensen’s similarity index showed that between all sites there was over 50 and 40% similarity of woody species and family, respectively (Table 1). The woody species in the open grazing land were less similar to the woody species in the area exclosures, whereas the similarity of woody species between exclosure was higher than with the open grazing land. Of the total woody species encountered in the study area, six were common in all the exclosures and open grazing land and 11 species were present only in the exclosures. One woody species (Prosopis juliflora) was only recorded in the open grazing land and three woody species (Balanites aegyptiaca, Berchemia discolor, and Grewia ferruginea) were recorded only in the young age exclosure. The existence of Prosopis juliflora indicated that there is an encroachment of exotic and invasive tree species on the degraded open grazing land. Reports have indicated that certain woodlands in the Eastern Ethiopian highlands are causing some socio-cultural damage (FAO, 2015). In the study area and the nearby Afar region, the encroachment of Prosopis juliflora is becoming a great concern to the communal rangeland.

| Land use | Species similarity (%) | Family similarity (%) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OGL | Yo-ex | Mi-ex | Ol-ex | OGL | Yo-ex | Mi-ex | Ol-ex | |

| Open grazing land | 100.00 | 51.85 | 58.33 | 58.33 | 100.00 | 40.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| Young age exclosure | - | 100.00 | 75.00 | 77.42 | - | 100.00 | 71.43 | 80.00 |

| Middle age exclosure | - | - | 100.00 | 93.33 | - | - | 100.00 | 93.33 |

| Old age exclosure | - | - | - | 100.00 | - | - | - | 100.00 |

Of the total family recorded in the study area, Fabaceae was observed in all the exclosures and open grazing land, and Olacaceae was only recorded in the young age exclosures. Only three family names, i.e., Boraginaceae, Fabaceae, and Tiliaceae were observed in the open grazing land (Tables 4-7). As in many other places of Ethiopia, the Fabaceae family contributed the greatest number of species in the study area (Mekuria and Yami, 2013; Mekuria et al., 2015; Gebremedihin et al., 2018). Despite its consistency, both family numbers and species numbers increase with an increase in age of exclosure.

| Land Use | Species Richness | Shannon Index (H’) | Shannon Evenness (E’) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Open grazing land | 10 | 0.74 | 0.32 |

| Young age exclosure | 17 | 2.02 | 0.71 |

| Middle age exclosure | 14 | 2.12 | 0.80 |

| Old age exclosure | 15 | 2.06 | 0.76 |

3.2. Woody Species Diversity

The Shannon-Wiener (H') index ranged from 0.74 at the open grazing land to 2.12 at the middle age exclosure (Table 2). According to Magurran, (2004), the Shannon-Wiener (H')diversity index in the exclosures can be rated as moderate whereas the diversity in the open grazing land was very low. Usually, the value of the Shannon-Wiener diversity index ranged from 1.5 to 3.5 and rarely superpassed 4 for a very huge number of species (Magurran, 2004). Shannon-Wiener diversity index in the study area indicated that exclosures can improve the diversity of woody species in the degraded open grazing lands. The changes in species richness were also evident in the Shannon-Wiener. The mean value of the Shannon-Wiener index of this study is in line with other similar studies conducted by Mekuria et al., (2018) in West Gojam, North-Western Ethiopia, and Gebremedihin et al., (2018) in the highlands of Tigray, Northern Ethiopia.

The Shannon evenness (E) index was also lower (0.32) at the grazing land and it was higher (0.80) in the middle age exclosure (Table 2). The higher the evenness value, the more even the distribution of species is at a site (Kent, 2012). Thus, the result of this study showed that there was a better equitable distribution of individual woody species in the exclosure than open grazing land. The high Shannon evenness value in the middle age exclosure might be attributed to the low anthropogenic disturbance in the exclosures since it is excluded from unmanaged access. In line with this study Teketay et al., (2018) reported an evenly distributed individual of woody species in area exclosure than in the open grazing area in Mopane woodland in northern Botswana.

3.3. Woody Species Structure

3.3.1. Basal Area and Tree Density

As indicated in (Table 3), significantly (p < 0.05) higher woody species basal area was observed in the middle (20 m2 ha-1) and old age exclosure (20 m2 ha-1) than the young age exclosure (6 m2 ha-1) and open grazing land (3 m2 ha-1). This indicated an increase of volume and area occupied by woody species with exclosure age. The highest basal area in the exclosures could be due to the relatively long period of exclusion from interference which allowed woody species to grow bigger. Other similar studies conducted in North-Western Ethiopia by Mekuria et al., (2018) and in Eastern Tigray, Ethiopia by Birhane et al., (2007) reported higher basal area in area exclosures than adjacent open grazing lands. Furthermore, the mean woody species basal area of exclosures was higher than other similar studies conducted in different parts of Ethiopia (Mekuria et al., 2018; Haftom et al., 2019).

| Land Use | Basal Area (m2 ha-1) | Tree Density (ha-1) |

|---|---|---|

| Open grazing land | 3.54±1.75b | 200.00±44.10b |

| Young age exclosure | 6.29±1.54b | 469.44±28.50a |

| Middle age exclosure | 20.35±3.92a | 483.33±26.02a |

| Old age exclosure | 20.29±5.09a | 559.33±81.86a |

| p-value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| CV% | 81.26 | 35.28 |

Tree density showed a significant difference (p < 0.05) between exclosures and the open grazing lands. It was ranged from 200 trees ha-1 in the grazing land to 559 trees ha-1 in the old age exclosure (Table 3). Tree density showed an increasing trend with increasing age of the exclosure. It is observed in this study that woody species density was positively influenced by exclosures. The tree density in the old exclosure was two and a half times higher than the tree density in the open grazing land. Similar studies were conducted by Mekuria et al., (2018) in West Gojam, North-Western Ethiopia, and by Teketay et al., (2018) in Mopane woodland in northern Botswana which showed a higher woody species density in exclosure than their adjacent grazing land. However, compared to these studies, the mean tree density in the study area was very small. This might attribute to differences in the management practice of the exclosures.

| Species Names | Family | TD | RF | RA | RD | IVI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acacia tortilis (Forssk.) Hayne. | Fabaceae | 53.13 | 17.24 | 22.37 | 34.35 | 73.96 |

| Acacia nilotica (L.) Willd. Ex Del. | Fabaceae | 37.5 | 6.9 | 15.79 | 24.44 | 47.12 |

| Acacia etbaica Schweinf. | Fabaceae | 43.75 | 13.79 | 18.42 | 11.22 | 43.43 |

| Acacia senegal (L.) Willd. | Fabaceae | 15.63 | 13.79 | 6.58 | 15.05 | 35.43 |

| Dichrostachys cinerea (L.) Wight & Am. | Fabaceae | 28.13 | 10.34 | 11.84 | 2.9 | 25.09 |

| Ehretia cymosa Thonn. | Boraginaceae | 15.63 | 10.34 | 6.58 | 3.23 | 20.15 |

| Acacia seyal Del. | Fabaceae | 12.5 | 6.9 | 5.26 | 7.48 | 19.64 |

| Grewia villosa Willd. | Tiliaceae | 15.63 | 10.34 | 6.58 | 0.47 | 17.39 |

| Acacia brevispica Harms. | Fabaceae | 12.5 | 6.9 | 5.26 | 0.54 | 12.7 |

| Prosopis juliflora (Sw.) DC. | Fabaceae | 3.13 | 3.45 | 1.32 | 0.33 | 5.09 |

| - | - | - | 100 | 100 | 100 | 300 |

3.3.2. Important Value Index

Analysis of IVI species in the open grazing land showed that Acacia tortilis (74%), Acacia nilotica (47%), and Acacia etbaica (43%) were the most important valued species (Table 4). In the young age exclosure Acacia brevispica (82%), Acacia tortilis (58%), and Dichrostachys cinerea (24%) were woody with high IVI value (Table 5). Acacia senegal (67%), Acacia brevispica (61%), and Acacia nilotica (58%) in the middle age exclosure (Table 6) and Acacia senegal (99%), Acacia nilotica (57%), and Acacia brevispica (36%) in old exclosure (Table 7) were the woody species which had high IVI value. Analysis of IVI in the study area showed that Acacia senegal was one of the woody species which make the top five IVI species across all the exclosures and the open grazing land. In addition to this, Acacia brevispica is one of the species which makes the top five IVI species in all the exclosures.

The IVI result has also shown that Acacia tree species were the most ecologically important species in both grazed and exclosures. The importance value index indicated the relative ecological importance of the woody species in the study area (Kent, 2012). The dry lowland area of Ethiopia is known for its dominance by Acacia tree species (Mengistu et al., 2005; Nyssen et al., 2008b; Birhane et al., 2010; Yimer et al., 2015). Feyisa et al., (2017) in Borana rangelands, Southern Ethiopia has reported that Acacia tortilis, Acacia seyal, and Balanites aegyptiaca dominated exclosure. Acacia species are among the common woody plants that naturally grow in many dry rangelands in sub-Saharan Africa (Yayneshet et al., 2008). These species are important litter producers in the exclosures established on degraded lands (Descheemaeker et al., 2006a) and subsequently, improve soil fertility (N2-fixing) and increase SOC stock (Nair et al., 2009; Abaker et al., 2016).

| Species Names | Family | TD | RF | RA | RD | IVI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acacia brevispica Harms. | Fabaceae | 205.56 | 4.55 | 43.79 | 34.5 | 82.83 |

| Acacia tortilis (Forssk.) Hayne | Fabaceae | 41.67 | 15.91 | 8.88 | 32.73 | 57.52 |

| Dichrostachys cinerea (L.) Wight & Am. | Fabaceae | 38.89 | 13.64 | 8.28 | 2.07 | 23.99 |

| Acacia senegal (L.) Willd. | Fabaceae | 13.89 | 9.09 | 2.96 | 11.83 | 23.88 |

| Euphorbia cactus Boiss. | Euphorbiaceae | 55.56 | 9.09 | 11.83 | 0.65 | 21.57 |

| Delonix regia (Boj. ex Hook.) Raf. | Fabaceae | 16.67 | 9.09 | 3.55 | 3.58 | 16.22 |

| Acacia nilotica (L.) Willd. Ex Del. | Fabaceae | 13.89 | 4.55 | 2.96 | 8.66 | 16.16 |

| Euclea divinomm Murr | Ebenaceae | 27.78 | 6.82 | 5.92 | 0.2 | 12.94 |

| Grewia villosa Willd. | Tiliaceae | 11.11 | 6.82 | 2.37 | 0.17 | 9.36 |

| Grewia bicolor Juss. | Tiliaceae | 13.89 | 4.55 | 2.96 | 0 | 7.51 |

| Balanites aegyptiaca (L.) Del. | Balanitaceae | 2.78 | 2.27 | 0.59 | 3.52 | 6.39 |

| Berchemia discolor (Kiotzsch) Hemsl. | Rhamnaceae | 11.11 | 2.27 | 2.37 | 1.35 | 5.99 |

| Grewia ferruginea Hochst. ex A. Rich. | Tiliaceae | 5.56 | 2.27 | 1.18 | 0.02 | 3.48 |

| Acacia oerfota (Forssk.) Schweinf. | Fabaceae | 2.78 | 2.27 | 0.59 | 0.56 | 3.43 |

| Ziziphus spina-ehristi (L.) Des. | Rhamnaceae | 2.78 | 2.27 | 0.59 | 0.1 | 2.96 |

| Ximenia americana L. | Olacaceae | 2.78 | 2.27 | 0.59 | 0.04 | 2.9 |

| Acacia seyal Del. | Fabaceae | 2.78 | 2.27 | 0.59 | 0 | 2.87 |

| - | - | - | 100 | 100 | 100 | 300 |

| Species names | Family | TD | RF | RA | RD | IVI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acacia senegal (L.) Willd. | Fabaceae | 113.9 | 12.5 | 17.83 | 36.27 | 66.59 |

| Acacia brevispica Harms. | Fabaceae | 197.2 | 12.5 | 30.87 | 17.41 | 60.78 |

| Acacia nilotica (L.) Willd. Ex Del. | Fabaceae | 80.56 | 12.5 | 12.61 | 32.66 | 57.77 |

| Delonix regia (Boj. ex Hook.) Raf. | Fabaceae | 47.22 | 9.72 | 7.39 | 5.61 | 22.73 |

| Euphorbia cactus Boiss. | Euphorbiaceae | 61.11 | 9.72 | 9.57 | 1.97 | 21.25 |

| Grewia bicolor Juss. | Tiliaceae | 27.78 | 6.94 | 4.35 | 1.56 | 12.85 |

| Ehretia cymosa Thonn. | Boraginaceae | 16.67 | 6.94 | 2.61 | 2.06 | 11.61 |

| Grewia villosa Willd. | Tiliaceae | 25 | 5.56 | 3.91 | 1.24 | 10.71 |

| Dichrostachys cinerea (L.) Wight & Am. | Fabaceae | 16.67 | 5.56 | 2.61 | 0.02 | 8.18 |

| Euclea divinomm Murr | Ebenaceae | 22.22 | 4.17 | 3.48 | 0.02 | 7.66 |

| Apodytes dimidiata E. Mey. Ex Am. | Icacinaceae | 8.33 | 4.17 | 1.3 | 0.51 | 5.98 |

| Acacia etbaica Schweinf. | Fabaceae | 8.33 | 4.17 | 1.3 | 0.01 | 5.48 |

| Acacia tortilis (Forssk.) Hayne | Fabaceae | 8.33 | 2.78 | 1.3 | 0.67 | 4.75 |

| Acacia oerfota (Forssk.) Schweinf. | Fabaceae | 2.78 | 1.39 | 0.43 | 0 | 1.83 |

| Ximenia americana L. | Olacaceae | 2.78 | 1.39 | 0.43 | 0 | 1.83 |

| - | - | - | 100 | 100 | 100 | 300 |

| Species names | Family | TD | RF | RA | RD | IVI |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Acacia senegal (L.) Willd. | Fabaceae | 181.3 | 17.78 | 32.4 | 49.18 | 99.36 |

| Acacia nilotica (L.) Willd. Ex Del. | Fabaceae | 78.13 | 13.33 | 13.97 | 29.21 | 56.51 |

| Acacia brevispica Harms. | Fabaceae | 106.3 | 13.33 | 18.99 | 4.09 | 36.42 |

| Acacia tortilis (Forssk.) Hayne | Fabaceae | 18.75 | 8.89 | 3.35 | 9.71 | 21.96 |

| Acacia etbaica Schweinf. | Fabaceae | 21.88 | 8.89 | 3.91 | 6.69 | 19.49 |

| Euphorbia cactus Boiss. | Euphorbiaceae | 53.13 | 8.89 | 9.5 | 0.11 | 18.5 |

| Apodytes dimidiata E. Mey. Ex Am. | Icacinaceae | 28.13 | 6.67 | 5.03 | 0.05 | 11.74 |

| Dichrostachys cinerea (L.) Wight & Am. | Fabaceae | 21.88 | 4.44 | 3.91 | 0.51 | 8.86 |

| Delonix regia (Boj. ex Hook.) Raf. | Fabaceae | 15.63 | 4.44 | 2.79 | 0.08 | 7.32 |

| Ximenia americana L. | Olacaceae | 15.63 | 2.22 | 2.79 | 0.21 | 5.23 |

| Euclea divinomm Murr | Ebenaceae | 6.25 | 2.22 | 1.12 | 0.01 | 3.35 |

| Ziziphus spina-ehristi (L.) Des. | Rhamnaceae | 3.13 | 2.22 | 0.56 | 0.12 | 2.9 |

| Ehretia cymosa Thonn. | Boraginaceae | 3.13 | 2.22 | 0.56 | 0.01 | 2.79 |

| Grewia bicolor Juss. | Tiliaceae | 3.13 | 2.22 | 0.56 | 0.01 | 2.79 |

| Grewia villosa Willd. | Tiliaceae | 3.13 | 2.22 | 0.56 | 0 | 2.79 |

| - | - | - | 100 | 100 | 100 | 300 |

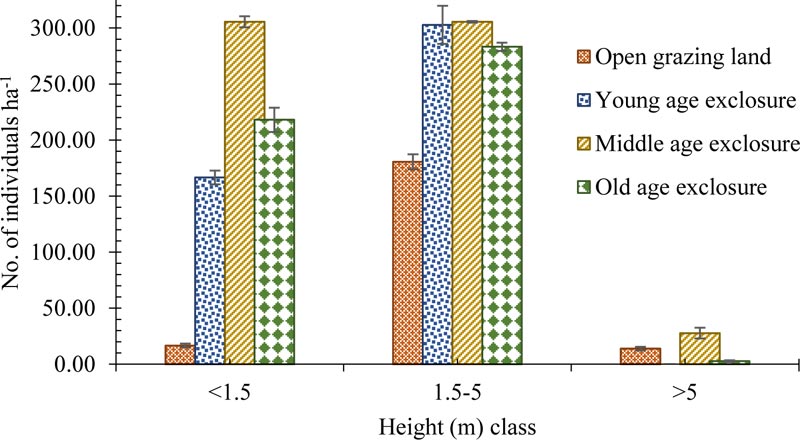

3.3.3. Population Structure

The majority of the woody species in the study area had a height of below 5 m. The mean height of woody species was higher in the area exclosures than the open grazing land. Relatively the middle age exclosure and open grazing land have a higher number of woody species individuals > 5 m height (Figs. 2 and 4). The mean height of the species was 2.96±0.14, 2.37±0.08, 2.23±0.09, and 2.24±0.09 m for open grazing land, young, middle and old age exclosure, respectively, with the maximum height observed for Acacia brevispica and Acacia senegal (6.2 m) and the minimum for Apodytes dimidiate (0.2 m).

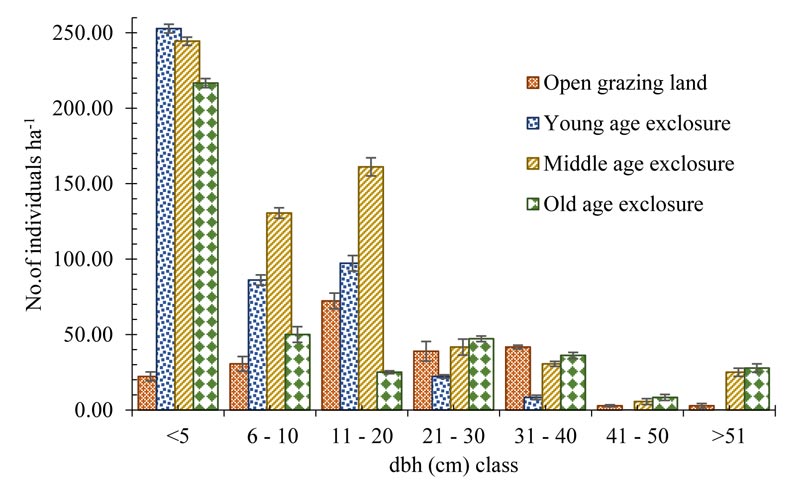

Diameter distribution of the community of all woody species in the study area showed an inverted J shape (Fig. 3). In open grazing land, most of the woody species were in the middle diameter classes (11-20 cm) and less in the lower diameter classes. The mean diameter of individual woody species was 16.91±0.99, 9.30±0.71, 14.62±0.98, and 14.80±1.17 cm for open grazing land, young, middle, and old exclosure, respectively. The dominance of remnant trees which are old, large and taller trees and less scattered existence of saplings and younger trees in the open grazing land might be the reason for the higher mean diameter of individual trees in the open grazing land than the exclosure. The maximum diameter was observed for Acacia senegal (80 cm) and the minimum for Dichrostachys cinerea, Grewia villosa, Ximenia americana, and Acacia brevispica (3 cm).

Both the height and diameter distribution graphs (Figs. 2 and 3) of this study depict that the open grazing land was dominated by shrubs and trees while exclosures had a higher number of tree seedlings and saplings. Thus, exclusion of disturbance favored the higher number of seedlings and saplings. Furthermore, the inverted J shape distribution of woody species dbh in the exclosures indicated that exclosure created favorable conditions for an active and uniform regeneration of woody species in the degraded and open grazing land. The higher mean height and diameters of woody species in grazing land might be due to seedlings and saplings exposed to domestic animals grazing and trampling. Due to exclusion from interference, there is a high probability of growing to the next diameter class in exclosures, that gives a better population structure. Similar investigations conducted in the highlands of Tigray, Northern Ethiopia by Negussie et al., (2008), and Birhane et al., (2017) have reported a higher abundance of tree seedling than adjacent open grazing lands. Other study by Teketay et al., (2018) also found higher seedling density in area exclosure than the adjacent open grazing system in Mopane woodland in northern Botswana.

3.4. Aboveground Woody Biomass and Carbon Stock

Aboveground biomass and belowground biomass showed statistically significant (p < 0.05) variation between exclosures and open grazing land (Table 8). Aboveground biomass ranged from 12.60 Mg ha-1 at the open grazing land to 86.61 Mg ha-1 in the middle age exclosure. Aboveground biomass quantified in this study mirrored the basa area which is significantly higher in the middle and old age exclosures. This might explain the higher AGB in the middle and old age exclosures. In a study undertaken Mekuria et al., (2018) in North-Western Ethiopia, it was indicated that exclosure land management can improve soil properties, which consequently supports the restoration of native vegetation and the accumulation of aboveground biomass. The result of this study is in line with findings of Yayneshet, (2011) in the Tigray region of northern Ethiopia and Mekuria and Yami, (2013) in the lowlands of Northern Ethiopia which reported higher aboveground biomass in exclosures than adjacent grazing lands.

Table 8.

| Land Use | AGB | BGB | AGB-C | BGB-C |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Open grazing land | 12.60±6.20b | 3.15±1.55b | 5.92±2.91b | 1.66±0.82b |

| Young age exclosure | 22.81±5.26b | 5.70±1.31b | 10.72±2.47b | 3.00±0.69b |

| Middle age exclosure | 68.61±12.47a | 17.15±3.12a | 32.25±5.86a | 9.03±1.64a |

| Old age exclosure | 67.85±15.96a | 16.96±3.99a | 31.89±7.50a | 8.93±2.10a |

| p-value | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 | < 0.001 |

| CV% | 76.21 | 76.21 | 76.21 | 76.2 |

AGB = Aboveground biomass, BGB = Belowground biomass, and C = Carbon.

The AGB carbon stock was significantly (p < 0.05) higher in the middle (32 Mg ha-1) and old (31 Mg ha-1) age exclosures whereas it was significantly lower in the open grazing land and young age exclosure. The BGB carbon stock followed a similar trend to the AGB carbon stock. The highest AGB carbon stock in the middle and old age exclosure could be associated with the high tree density and tree basal area. Except in the young exclosure, AGB and carbon stock had shown consistent increase from middle age to old exclosure age (Table 8). In line with this, several studies have indicated a significantly higher AGB carbon stock in exclosure than adjacent open grazing lands. For instance, studies conducted by Shimelse et al., (2017) in Tigray and Bikila et al., (2016) in Borana, North and Southern Ethiopia, have reported a significantly higher AGB carbon stock in exclosures than open grazing land. Another study by Mekuria and Yami, (2013) also displayed higher AGB in exclosures when compared to the adjacent communal grazing lands.

More importantly, this study demonstrated that pronounced woody biomass carbon can be stocked in the long-term. Generally, excluding degraded landscapes from free access of domestic animals and humans might bring an overall ecological restoration to the sites. Thus, such a restoration mechanism might contribute to the efforts of mitigating climate change in developing counties. A study by Witt et al., (2011) indicated a pronounced woody biomass carbon stock and significant ecological change following long-term grazing exclusion.

CONCLUSION

This study evaluated the influence of different ages of exclosure and adjacent open grazing land on woody vegetation structure, composition, and aboveground biomass carbon stock in the central dry lowland of Ethiopia. The results demonstrate that a considerable amount of woody species was restored due to the exclusion of open grazing land for rehabilitation purposes. Furthermore, woody species structure i.e., basal area, tree density, and composition were significantly influenced by age of exclosures. Excluding grazing animals and human interferences from accessing severely degraded lands for long period resulted in an approximate doubling of the tree density, standing basal area, species diversity, aboveground biomass, and carbon stock relative to grazed areas. The significantly higher aboveground biomass and aboveground biomass carbon stock clearly showed that degraded land restoration strategies through exclosure can sequester a large quantity of atmospheric carbon dioxide. To comprehend more on the impact of area exclosures on carbon stock, further investigation on belowground biomass and soil carbon stock is suggested.

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

| AGB | = Aboveground Biomass |

| BGB | = Belowground biomass |

| H' | = Shannon-Wiener diversity index |

| BA | = Basal Area |

| dbh | = Diameter at breast height |

| HSD | = Honest Significant Difference |

| IVI | = Importance Value Index |

| RA | = Relative Abundance |

| RD | = Relative Dominance |

| RF | = Relative Frequency |

CONSENT FOR PUBLICATION

Not applicable.

AVAILABILITY OF DATA AND MATERIALS

Not applicable.

FUNDING

Not applicable.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors declare that they have no any conflict of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Debre Birhan University, Ethiopia is duly acknowledged for the assistance of this study.

REFERENCES

[CrossRef Link]

[CrossRef Link]

[CrossRef Link]

[CrossRef Link]

[CrossRef Link]

[CrossRef Link]

[CrossRef Link] [PubMed Link]

[CrossRef Link]

[CrossRef Link] [PubMed Link]

[CrossRef Link]

[CrossRef Link]

[CrossRef Link]

[CrossRef Link]

[CrossRef Link]

[CrossRef Link]

[CrossRef Link]

[CrossRef Link]

[CrossRef Link]

[CrossRef Link]

[CrossRef Link]

[CrossRef Link] [PubMed Link]

[CrossRef Link]

[CrossRef Link]

[CrossRef Link]

[CrossRef Link]

[CrossRef Link]

[CrossRef Link]

[CrossRef Link]

[CrossRef Link]

[CrossRef Link]

[CrossRef Link] [PubMed Link]

[CrossRef Link]

[CrossRef Link]

[CrossRef Link]

[CrossRef Link]

[CrossRef Link]

[CrossRef Link]

[CrossRef Link]